The Life & Art of Karl Buesgen

Karl H. Buesgen, Sr. (1916 – 1981) was an American landscape painter and Pennsylvania impressionist typically associated with the Baum Circle, a group of artists either taught by, associated with, or directly influenced by Pennsylvania impressionist painter Walter Emerson Baum.

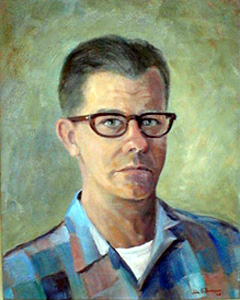

Friendship and love of the outdoors united Buesgen and Berninger

Portrait of Karl Buesgen, as painted by John E. Berninger.

June 23, 2005 | By Geoff Gehman of The Morning Call – Allentown, Pennsylvania

The Karl H. Buesgen Sr. show at the Baum School of Art has three stories as tight as Russian nesting dolls.

There is the story of Buesgen’s bucolic paintings of the Lehigh Valley, his Currier & Ives love of local landscapes. There is the story of his abiding friendship with his former teacher, John Berninger, his painting partner for 40 years of Sunday afternoons. And there is the story of Buesgen’s wife and their three children, who are thrilled that this respected, humble church musician is being recognized as an artist 25 years after his death.

The story really begins in the late 1930s, when Buesgen saw a Berninger landscape in the window of the Wuchter and Berninger jewelry store on Hamilton Street between 10th and 11th streets. Like many pedestrians, he took the bait and entered the store, where he found more paintings that Berninger liked to sell as necessary accessories to his jewelry. It didn’t take long for Buesgen to discover he had much in common with Berninger, who was 19 years older and six inches smaller.

Both men studied with Walter E. Baum, the pioneer Pennsylvania Impressionist, at the Kline-Baum School in their native Allentown. Berninger had taught at the school until the early ’30s, when Buesgen was apprenticing as organist/music director at Sacred Heart Church, an alley from where he grew up. Both believed in Baum’s belief that the outdoors could only be painted faithfully outdoors.

Buesgen became Berninger’s student, art partner and location scout. He and Berninger returned often to magnetic spots: a red barn between Little Gap and Kunkletown; an old mill by Jordan Creek at Bittner’s Corner in Weisenberg Township. Working side by side, they centered paintings with paths and bodies of water, turning causeways into compasses. They changed the nature of nature, transforming roads into rivers, glazing branches with chalky Cezanne clays. For them, the outdoors was one giant palette. The pond in Buesgen’s “Summer Pond,” for example, is a kaleidoscope of olive smudges, brown squiggles and brackish pinks.

Buesgen became Berninger’s student, art partner and location scout. He and Berninger returned often to magnetic spots: a red barn between Little Gap and Kunkletown; an old mill by Jordan Creek at Bittner’s Corner in Weisenberg Township. Working side by side, they centered paintings with paths and bodies of water, turning causeways into compasses. They changed the nature of nature, transforming roads into rivers, glazing branches with chalky Cezanne clays. For them, the outdoors was one giant palette. The pond in Buesgen’s “Summer Pond,” for example, is a kaleidoscope of olive smudges, brown squiggles and brackish pinks.

In their pictures humanity is always harmonious. Buesgen’s “Sleigh Ride” is a charmingly giddy scene of a trip down a snowy lane with a barn and a church as folksy guardians. In this Spielbergian fantasy one expects the sled to do an E.T. on a bicycle and fly over whipped-cream hills into a meringue sky.

Berninger was the livelier painter. His autumn leaves are wispier; the cake frosting on his waterfalls is tastier. Perhaps his pictures are more charismatic because he was. He was the extrovert, the chronic dry jester. He loved to repeat his translation of composer Rimsky-Korsakov’s name as “Rinse Your Coffee Cup.” Buesgen was the introvert, the philosophical humorist. He liked to repeat “This too shall pass” whether he was amused or bothered, whether he was addressing a bruised ego or torn knee ligaments.

According to his relatives, Buesgen rarely lost his temper. The one time he did was on his first painting expedition with his daughter, Mary Catherine. Despite his warnings to stay clear of Jordan Creek, she fell in. Decades later, she recalls the ride back to the family home on Gordon Street seemed to last an eternity. It ended with Buesgen brusquely telling his wife, Louisa: “Here she is. She ruined my day.” It would be the last time father and daughter shared an art adventure.

Buesgen and Berninger w eren’t adventurous outdoorsmen. Unlike Edward Redfield, they didn’t paint in snow above their knees. Unlike Redfield, they didn’t tie canvases to trees to keep them from blowing away. During bad weather they stayed away from the woods, areas Berninger dubbed “the hinterland.” Instead, they worked in the third-floor studio of Berninger’s house at 15th and Turner streets, across from West Park. To warm themselves in the chilly room, they wore gloves cut off at the fingertips and listened to WFLN, then Philadelphia’s classical-music beacon.

eren’t adventurous outdoorsmen. Unlike Edward Redfield, they didn’t paint in snow above their knees. Unlike Redfield, they didn’t tie canvases to trees to keep them from blowing away. During bad weather they stayed away from the woods, areas Berninger dubbed “the hinterland.” Instead, they worked in the third-floor studio of Berninger’s house at 15th and Turner streets, across from West Park. To warm themselves in the chilly room, they wore gloves cut off at the fingertips and listened to WFLN, then Philadelphia’s classical-music beacon.

Berninger and Buesgen even collaborated on paintings of scenes they didn’t paint together. Berninger took slides of Maine’s rocky coast that Buesgen turned into seascapes. He never actually visited Bar Harbor, mainly because he was too busy playing organ at Mass and singing at weddings. The closest he got was the New Jersey shore, traveling with his family and a colleague who tuned pipe organs.

This priceless partnership ended in February 1980 when Buesgen suffered a stroke. Paralyzed and speechless, he couldn’t paint or sing, his favorite activities. As often happens with any kind of long union, Buesgen and Berninger died the same year. Berninger passed away in July 1981; Buesgen followed him five months later.

Twenty-five years later, the Bs are still shadowing one another. Buesgen’s show opened at the Baum School this month, nine months after the school presented an exhibition of Berninger’s landscapes. During the opening reception visitors kept asking Buesgen’s relations why they kept his painting such a secret. They explained that he considered his music more important than his art, that he painted primarily for himself, his family and his best friend.

“Painting was a hobby to Pop and Mr. B; it wasn’t a job,” says Joe Buesgen, his father’s archivist. “They weren’t looking to sell their paintings. They just found a certain…” — his mother fills in the missing word — “… outlet.”

The Baum exhibit fulfills Joe Buesgen’s goal of spotlighting his father’s art 25 years after his death. “Pop is finally being appreciated outside the family,” he says. “He’s finally coming into his own.”

Republished with permission of The Morning Call. All Rights Reserved.